Hey there,

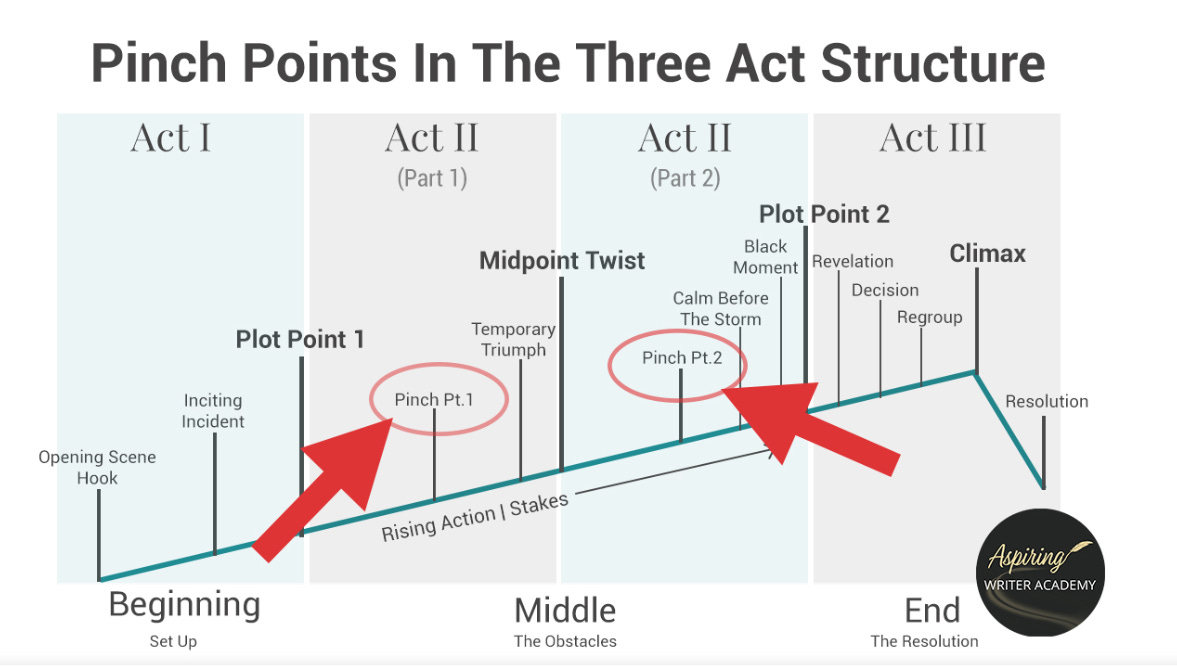

have you seen this chart before—maybe once, twice, ten times? I pulled this particular, useful graphic from one of many online sites that advise writers to structure a novel essentially like a conventional, big budget screenplay, around plot points and “pinch points”. Plot points are the larger turning points, reversals of fortune, power exchanges, highs and lows, reveals and handoffs. Pinch points are essentially moments working in support of the larger drama in what might be smaller, related ways or secondary storylines. The two work in concert to keep a sense of escalating tension, always raising the stakes.

If you’re working on a novel, holding this structure in mind (and in your notes) can be a helpful way to think about an overall trajectory, paying attention to where the storyline needs to go: upward, toward a big…climax!

It’s about keeping your eye on the story’s horizon.

I was thinking about this essential structure the other day, talking about the question of burning out while drafting a novel. It’s easy to come up with a general character idea, pick a POV and a narrative voice, put a few scenes together, get a good start, then…walk away from a novel/project. It’s possible to eventually circle back around, maybe start a new novel, take another run at it, again with a few good scenes, some dialogue…and do the whole false-start again, once again losing momentum. Get 20 or 40 pages in, and question where it’s all going…

If you need a way to keep the end in sight as you generate a first-draft, consider this structure as broad overview, offering a sense of what can happen up ahead and how events build on each other within the world of your book.

Caveat: You also don’t need to adhere to this structure at all. Keep some essential joy in your process. Ask yourself what you’d like to say or show or make. What goes on your pages? Maybe your vision isn’t exactly a steady, rising action…

This singular idea of the shape of a story structure is based on so much that we as a culture might assume…about art, and about life…There’s more than one way to tell a story, just like there’s more than one way to get dressed every day, and more than one way to relate to the natural world.

At the risk of swinging wide, here, I’m going to say…the standard, big biz structure follows or falls under the umbrella of Capitalism, as an economic theory that dominates all others, and colonization, as a way of life that dominates all others. Big plot points, rising action, a major pay off…the shark that can’t stop swimming, corporations that can’t stop increasing their revenue, a stock market chained to ever upward-ticking markets or risking collapse…

There are other ways of looking at a moment, a dynamic, a book, a life. Quieter ways, more associative ways, with contrasting emotions, hijinks and hard truth.

I come to writing through collecting details, guided by my own interests. These might be ideas, images, dialogue, interactions or other. I put rough sketches side-by-side, and consider what it is I want to say, show or spend time with, and what kind of world I want to spend time in. I hold a sense of structure in mind in a more associative way: one event causes another.

My “inciting incident” might be allowed to be small; the details of life can at times propel larger drama, bigger dynamics. Plot is the overriding vehicle, a container for the smaller gestures. I start collecting, then build out, working on the shape of the work on the macro and the micro, and not every storyline needs to find the same form. Each novel can be…novel, unique to itself, while also recognizing a relationship to audience, including expectations. An author can determine the relationship between the work they make and existing audience expectations.

Part of the beauty of writing a novel is that it isn’t a multi-million dollar undertaking. It’s your book. It might become an indie best-seller, or a “big five” darling. It could be the grappling hook that soars out into the world or the draft, writing as a labor of love, that waits in a desk drawer, a place to put ideas. It’s all writing. It all matters.

There’s more than one way to build a novel, and it’s okay to let yourself follow your own impulses, too. Know the conventions (they’re not really “rules,” but instead habits, conventions, tried-and-true, well-worn, possible paths…) in order to break them.

I’m precisely, tenaciously ambivalent about the above graph’s particular structure. I’m all for it if it helps tell the story a writer wants to tell, build the world, reach readers. But it’s also very…Hollywood. It’s a boiled down well-worn template for constructing rising action, yanking the chain, keeping it growing. In part, how closely one adheres to this structure comes back to a question of audience.

When I first wrote my first novel, Clown Girl, it was a moody, low-key and sometimes inexplicable dreamworld…then I rewrote it, hammering in the baseboards a little more tightly, framing in the rooms, the world. When editors took an interest but corporate publishers chose to pass, I went back and put in a more conventional structure. I used the framework of a rom-com alongside a gritty clown world, and that made all the difference. When actress Kristin Wiig bought the film rights, she said, “You’ve written a three-act structure!” She seemed surprised. But of course I had, intentionally. It was a structure I applied to pull pieces into focus and make my intentions, as the author, more recognizable to a wider audience. It worked. And though Wiig didn’t end up making the film, the tenor influenced her romcom sensibility going forward.

I still love the first version—the awkward, moody, mumblecore of clowndom—but I cranked up a more conventional, underlying structure to get the work out into the world. Informed choices create options.

Here’s the thing—you can’t make these choices if you don’t get words on the page. If you want to write a novel, start by doing whatever it takes to motivate yourself to create a draft. Beginning, middle, end. Characters in conflict or in love, or love + conflict. Create a desperate situation, an urge toward greatness, life and death, sex and money, whatever draws your interest. Make a tossed salad of desire, then start sorting out the dynamic points, the hot spots.

Are you working on a novel? A screenplay?

I’m drafting another novel, now. I like it a lot. Once I’ve framed in all the rooms, I’ll step back, see how the structure is working, see how the pages turn, how the characters evolve, how the story unfolds.

xo

M

I like this piece a lot. It is an argument for returning writing to a passion and vision that will connect with some readers, but maybe not all. Such thinking is the antithesis of blockbuster books and the pitiful attempts of AI at writing.

Thanks for this, Monica. As a reader, and sometimes as a watcher of films and streaming series, I am boooooored with the predictable arcs and plots and pinches. (My least favorite: when the big reveal toward or at the climax ends up being the revelation of a fact or story that the narrator and/or lead character has known the entire time.)

I understand how these things function. I get that structure matters. I'm a small-town newspaper writer and columnist now; I've got the 800-word article down pat. When I wrote short stories (and got most of them published) I didn't feel the need for structure. Writing short fiction was like writing a poem; it wrote itself.

Now I'm attempting a novel. I want structure, sure, but I don't want the cornball same old thing. I love the fantasy genre for YA or middle readers, some of the adult stuff too. But so many of these books and films insist on an over-the-top, Hollywood, downright dumb climax. My brain and emotional system click out when the battle is too ridiculous or the orchestral swells too manipulative. Do readers and viewers insist on this? Or do publishers and producers just imagine that their audiences want this?