*Not sure why the glitch when I sent this out earlier. The first photo showed up three times? Maybe this is better! xo

To circle back around, to pick up where I left off, to use a couple of very physical, body-centered ways of saying…look, remember?

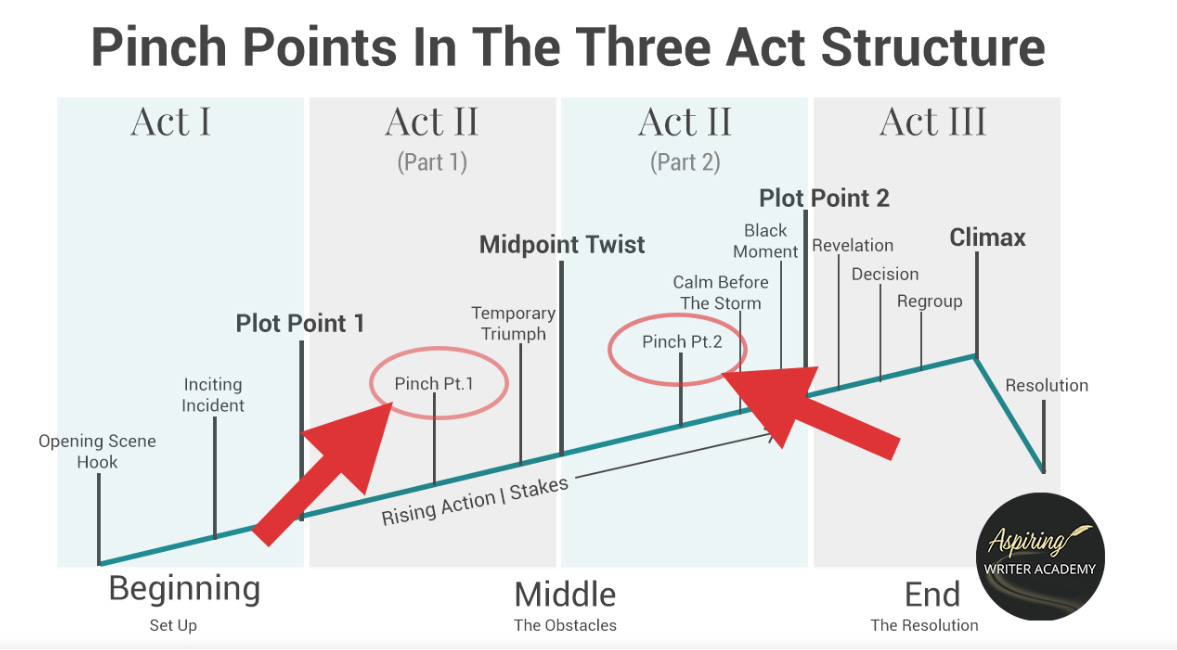

We were talking about literary conventions, intuition, generally held techniques, structure—

And we were also talking about Stacey Levine’s novel, Mice 1961.

It makes senses then to consider the structure of this particular novel.

If you’ve worked with me in workshop or otherwise, you’ve probably heard me say, “Specifics do more work than generalities.” We started with general thoughts about structure. Now let’s move into specifics.

Levine’s novel is about a summer party in a small town of insiders and outsiders, blame, judgement and fear. Every character has quirks, and some appear more accepted than others. The narrator is a strange, embodied apparition, always hiding, sleeping behind the sofa and ducking into bushes to watch the two sisters at the heart of the drama navigate the town’s gossipy cold shoulder. A question is implied: Will they survive? Will Mice run away with this narrator? Will Jody let go, and find romance or her own life?

While the story is about this externalized plot— insider/outsider dynamics, a summer party—it really seems to be more about the less tangible, very real question or concern of putting people—those wild animals, twisted psyches, loose cannons!—together in close proximity and witnessing ways humanity undoes itself. How do we get along at all? How do we save ourselves and each other, and how is harm inflicted?

Perhaps it’s a novel about the convergence of personalities, the collision of need and fear and want and love and loneliness. Those are the words that come forward for me: convergence, collision.

In the first chapter, two sisters are both rushing from different directions toward the site of the town’s spring party. They’re on a collision course, running both toward and away from each other, it seems. “At the intersection, [Jody] collided with a local police detective, grabbing his blue jacket….” (pg. 13). Of course she does! They’re all colliding.

This idea of rushing, running, separately but toward a shared goal, colliding with others on the way, seems central to the entire unfolding of narrative threads.

There’s an element of Levine’s storytelling that we brought up in our online conversation. (Thank you! To those of you who made it!)

The narrator recognizes or views life as story:

If it was clear to me on that day as to why the girl jumped into the cement depression and why she’d left the apartment so early when the sun was strong, less clear was where the story would go and where it might leave me. And if the story could ever hope to become itself.

The narrator imagines a “helper” will soon arrive and change the trajectory of the plot. The narrator actually worries about becoming less relevant, less necessary, once the anticipated yet unknown helper comes on the pages.

In conversation, Jesus Cabrales pointed out that that this delivery is very meta….(thank you!)

It’s the metafictional handling of the question of story, life, expectations, compulsions and essential social roles that taps the larger sprawl of charm and characters in this work more closely toward the shape of a novel’s conventions, without giving in entirely to the illusion, or to expectations.

It could be viewed as a “stranger comes to town” construction (a man the narrator considers the “helper” shows up near the end). But the sisters are also strangers who have come to town. The narrator is a stranger who has come to town. Maybe they all are, in this place, in this time, in their hearts. We only know what we’re told, through the POV of our awkward, nearly transparent smudge of a narrator, as she hides both her body and her longing, watches and reports back. Her’s is a decidedly subjective assessment.

Many say that life’s fable is prearranged. It’s a famous feeling, that sensation of fate. Some stories proceed as if fate were real. They try to beguile. Some keep up a frantic pace, and other stories scarcely move: wine pooling in the brain. Many finish in that celebrated, falsely conclusive way, the lacquered finish I both long for and cannot stomach. Some fail to see that a story is far more than a recounting of events. And certain stories stray to a faraway edge that tastes as unreal as saffron: metal crushed with honey.

I love the physicality of that last line, giving stories a taste, and trying to capture the taste of saffron of all things. I also love how this passage acknowledges the way we may want stories to be tidy, and we may simultaneously resist falsely tidy endings.

Not to give the wrong impression—most of the novel is about conveying characters, actions, dialogue. But once in a while the narrator breaks into this big voice, a philosopher’s voice, an artist’s voice, the storyteller:

I saw how real a story can be, even when untrue. In a world-sized skein of stories and dreams, various threads pull and ride atop each other; some break away while new versions form. This one, drawn from a yarn about two rival sisters, starts and ends on Reef Way, the boulevard that barrels the miles west from Miami into the Everglades.

That passage about the ending? It comes near the beginning. It reads differently, on a second time through this short novel. It isn’t a conclusion, though it sounds a bit like one. It’s a piece of the narrator’s knowledge laid out in time, looking back, collected through experience, setting the pace, the path.

I hope reading this novel and thinking about structure might grant any of you who are interested in writing novels permission to make the form your own.

More to say—always more to say!—but enough for now.

xo